This past weekend, we met up with a friend of my husband’s who he hasn’t seen since before we got married. After the logistical urban nightmare of agreeing on a place where we would meet (via email during her intermittent periods of wifi access), we gave up and squeezed ourselves into a tiny corner table at a cafe. We sat with our teapots, barely able to hear ourselves between the cacophony of a dad attempting to read a Madeline story to his fidgety daughter and a group of parents bemoaning the city’s competitive high school selection process.

The friend miraculously managed to find us (which is good, because we were not planning to go back out into the cold), and, after the introductions and pleasantries, she triumphantly unfurled her map of midtown, eagerly asking “So, where do you guys live?” We pointed to the place way off the map that would indicate our neighborhood, a full 130 blocks north of our current location. Then she asked where our respective commutes took us each day. My husband pointed smack in the center of the map: midtown. Then he smiled at me—he knew my answer would take a minute. Or twenty.

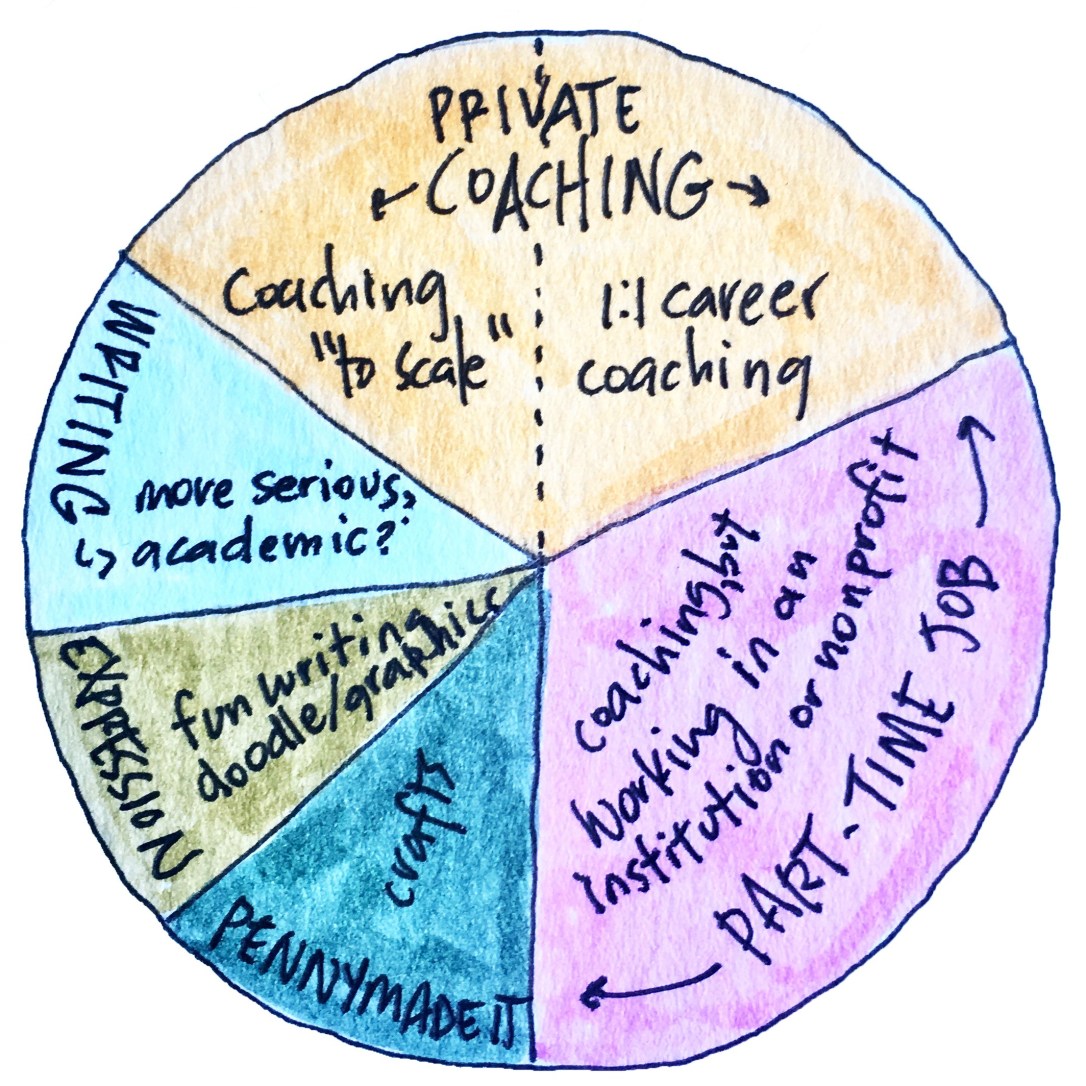

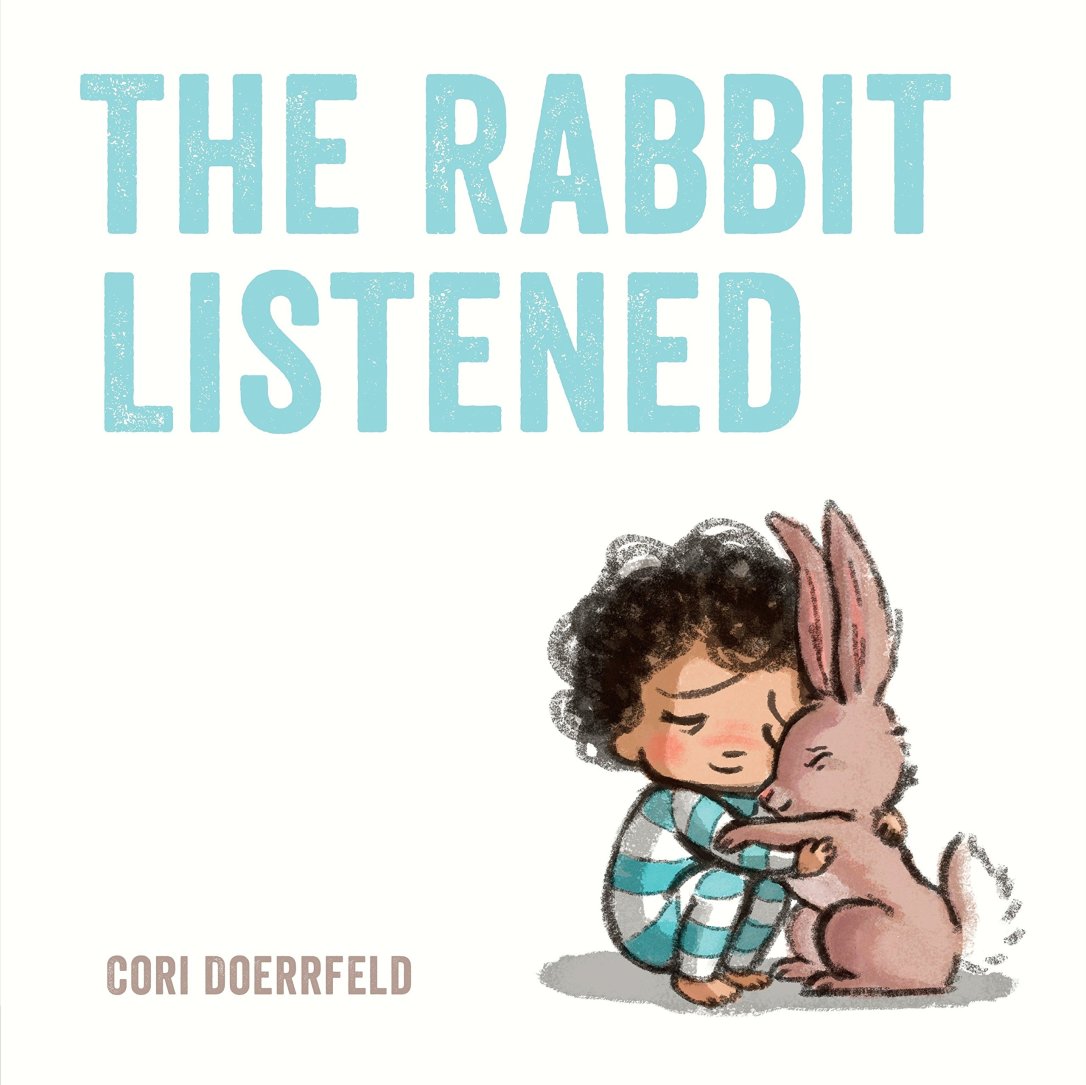

Unless I have class, I usually commute a full twenty feet to my home office these days, but there is something about saying this that still feels like defeat. Even though I am working with more focus than I ever have these days, It’s still easier to frame my answer in terms of where I used to work when I had a full-time job; it’s just an easier narrative for people to hear. I see her face turn into a question mark as I give my elevator speech about Narrative Medicine and my plans beyond graduation. So you’re doing career coaching for people who have chronic illness? Yes, that is my specialty, but I work with others as well. My proud husband chimed in with my various other projects: daily graphic medicine illustrations, volunteering with a hospice organization, working as part of the volunteer collective in my neighborhood bookstore, and co-writing and illustrating a children’s book. When he mentioned our craft business, I wondered whether she was thinking, “Wow, this woman has a lot of interests!” or “Damn, why can’t this woman decide what the hell her focus is?”

The judgment is mine, not hers, I am sure.

Why do I care so much, and what would it say about me if both of these things were equally true? Of course I want to make a good first impression on my husband’s friend. Almost four months post full-time employment, I’m still getting used to explaining what it is that I currently do. It was so much easier when I had a full-time job and thus, a quick answer: “I’m a teacher.” “I work in a startup.” “I work at a university.” Even “I’m a student” is fully true, but it doesn’t actually account for all that I am and how I spend the majority of my time. But people I’m just meeting don’t need to know all of this, anyway!

I have been so programmed to believe that if I am not producing, not earning at my maximum capacity, I am not contributing. But this is not fully true. I feel a greater sense of connection, satisfaction, and meaning from my six hours per week spent volunteering than I ever I did from sitting at a desk for 40-plus hours. What’s a better way to answer this what-do-you-do question? I could start with I am a teacher, a writer, an artist, and a coach, and talk about one of my projects. The story gets a little easier each time I tell it. I just have to keep talking.

And that diagram at the top of this post? That’s how I plan to divide my time once I’m done with school. Pie charts don’t have to be made with Excel, you know…

So, who prescribed your medicines in 1994?

So, who prescribed your medicines in 1994? Imagine creating a secret identity for yourself, and now you are strong and brave and unafraid. You are resourceful, ready to vanquish enemies. You are part of a worldwide tribe that energizes and supports you. You are doing things you never thought possible and feel exhilarated and challenged. You are mastering—not enduring—life! Sounds pretty good, right?

Imagine creating a secret identity for yourself, and now you are strong and brave and unafraid. You are resourceful, ready to vanquish enemies. You are part of a worldwide tribe that energizes and supports you. You are doing things you never thought possible and feel exhilarated and challenged. You are mastering—not enduring—life! Sounds pretty good, right?